Chapter Two – Paying for Nuclear Energy

Chapter Two – Paying for Nuclear EnergyCaldicott, p. 19:

The nuclear industry myth says that nuclear power costs only 1.7 cents per kilowatt hour, whereas coal costs 2 cents and gas-fired power costs 5.7 cents.What I find irritating about this statement is that Dr. Caldicott didn't even source NEI for the numbers. These came from us, and if she’s going to dog us, we at least want the recognition. The numbers were the 2004 production costs found here (PDF, now includes 2005 figures, which the production costs of coal and gas have increased.)

On the same page, she cites a report from the New Economics Foundation that concluded “that the cost of nuclear power has been underestimated by almost a factor of three.” Here’s a previous blog done on the NEF report about a year ago.

Caldicott, p. 19:

Indeed, the nuclear industry baldly provides false estimates of the financial cost of nuclear electricity, failing to account for the total nuclear fuel cycle, basing their numbers on incomplete data.Come on. This tells me two things: 1) she didn’t take the time to explore our Web site, where she can find a link to costs here, or 2) she did find it but wanted to paint the picture of false estimates based on one chart.

Caldicott, p. 24:

If the economics of nuclear power look so dismal, why is there suddenly a huge push by the nuclear industry for new reactor construction?Maybe it’s that the figures are not as “dismal” as she believes. Markets are always changing, and have changed more and more in favor of nuclear power. Fossil fuels, particularly natural gas and oil, have experienced higher prices and increased volatility (PDF).

CO2 emissions are coming under more and more scrutiny by governments, and it is only a matter of time before CO2 regulations are in place in the United States.

In addition, the Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook 2006, projects that the United States is going to need about 170 gigawatts of coal capacity by 2030. That’s equal to about 170 average-sized nuclear plants.

What these projections tell us is that the country is going to return to building baseload capacity. After about 15 to 20 years of building peaker plants (natural gas capacity), the United States will need baseload again by the middle of next decade. And what are the two options for baseload? Coal and nuclear. Perfect timing for nuclear.

Coal technology is becoming increasingly cleaner, especially with the latest technology -- the Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle coal plant. So far only a handful of IGCC plants have been built in the world, including two in the United States. According to a Wisconsin Public Service Commission draft report (PDF, p. 1):

As there is limited construction and operating experience with IGCC, there is a range of uncertainty in determining costs for IGCC.

Page 19 of the report details the projected capital costs for the technology. It’s about the same range of some estimates for new nuclear plants. And this is without CO2 sequestration.

I’m not trying to rail on the new coal technology because, in my opinion, it’s the advancement of technology that will reduce emissions eventually to nil. My point is to show that new coal and nuclear plants are in the same boat with regards to capital costs and uncertainty. And these are the two large-scale generating technologies that will be built over the next several decades.

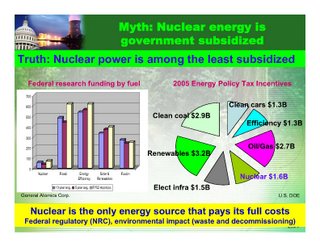

Back to Caldicott. Since we are discussing economics, you can imagine that subsidies soaked up quite a bit of ink in this chapter. Particularly regarding the latest energy bill. The only problem I have with this is that she does not show what incentives other energies received in the bill as well. Energy bills have not been passed without something for everyone.

According to slide 6 of an Entergy presentation (PDF), a pie chart shows the incentives received by all energy sources, as well as how much R&D funding has been received over the past decade. Nuclear was right smack in the middle of the pack for incentives received.

Economics is key to a sustained “nuclear renaissance.” The primary costs of concern are the construction costs due to the substantial amount of money needed to build a reactor. And of course, escalating costs are primarily what halted new-plant construction in the past.

Much has changed since then. Standardized designs, a one-step licensing process and simpler reactor technologies, to name a few factors, should make nukes much easier and faster to build. The key is getting over the uncertainties and hurdles of the first few new plants.

But it can be done and will be done, and we have confidence that the next generation of nuclear plants will be popping out on an assembly line over the next several decades.

Technorati tags: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Power, Electricity, Environment, Energy, Politics, Technology, Economics, Helen Caldicott

0 comments:

Post a Comment